Pay Attention

What to think about

I woke before dawn with no alarm and shuffled into boots, out from the bottom bunk and out of the room, not waking anyone, downstairs, to the great room to sit near the cold hearth to don gaiters, kitchen to fill the water bottle and stow an apple, an end of sourdough, hunk of cheddar and soppressata in foil, the door to the kitchen is double hinged, like a saloon, swinging silently, down the cement second stairwell and out, sequoias with snow turned to ice cradled in their roots, past the main road to the trailhead, the beginnings of catecholamine induced bronchial dilation, the tree line in view, down parka against the thinning, indifferent ether, frozen mud giving way to snow in earnest around 7,000, pinecones, a thin waterfall, then unpacked snow, snow that has not melted and frozen again in the sun, the sun that still has not risen but is paling the ridge line, headlamp stowed, lunar and stellar light fading, the silence between footsteps total. Up.

There’s a Baldy in New Mexico near where J Robert O and friends drank whiskey and rode horses and split the timeline, it may be owned by Ted Turner or the Boy Scouts or BLM, Tall Paul says, that’s Bureau of Land Management, not, you know. One of the state’s 12s, snow sometimes into the summer. California’s is a modest 10,000, he tells me the day before, but you are going to need crampons, an axe, probably rope, the whole nine, you want to go up in February after all this. There’s a lodge near the lift at 8,000, meet you there for a beer. There’s a Baldy in every state in the west, I think, Paul says.

Brooding, he said: something is wrong with the world. Why don’t we focus on you, she replied.

We are in the singularity. The density of information is so great that creation is impossible. There is just no space. The medium, to the extent it still fits the description, is infinitely compact. Everything is right here, right now.

The night before I had put down Neil Postman’s famous treatise1 with a kind of resigned exhaustion. His thesis, to paraphrase only slightly, was that in 1985, Americans were closer to a pleasure-induced Huxleyan dystopia à la Brave New World than to a censorship-induced Orwellian dystopia à la 1984. Go online2 and one finds that 2025 Americans are all very well aware of Big Brother and everyone is talking about how we are literally living in 1984. How the book is literally flying off the shelves. Postman posited that we were, in 1985, in not an Orwellian nightmare of truth manipulation and history reinvention by tyrants and censors, but instead a Huxleyan nightmare, wherein we were provided endless pleasure and uninterrupted positive stimulation (n.b.: the abbreviation, were it instead portmanteau, of social media as SoMe is almost exactly the same as the drug [Soma] that Huxley's wasted future humanoids consumed to keep themselves happily oblivious).

How did I come to be reading this book? Why, from a podcast of course! From Ezra Klein yammering incessantly about an attention economy and attention fracking. From his releasing another goldarn stinking episode every three days or so, which shows up on the Spotify App in the morning, when I open it, the App, when the traffic slows to 10 miles per, somewhere around White Oak, on the 101 E, but more recently around Canoga, and on some days even as early as fricking Topanga, the canyons still off limits because of the fires and then the mudslides, the notification shows up, an insouciant, pregnant, cornflower blue circle in the upper right corner of the podcast’s icon. It doesn’t matter to him if I listen to the newly released episode. He also doesn’t really care if I read any of the three books his guests recommend to the audience at the end of each episode. He’s frankly fine either way.

But Postman wouldn’t go away. Apart from Ezra constantly alluding to him, he had Chris Hayes on, who said, really, if he had just one book he thought everyone should read, and he knew it was an old one and had been recommended before, he still would recommend Amusing Ourselves to Death, by Neil Postman, he said, and furious to shut them the hell up, I went to the jungle on my batphone and one-click ordered the thing, to be delivered that afternoon.

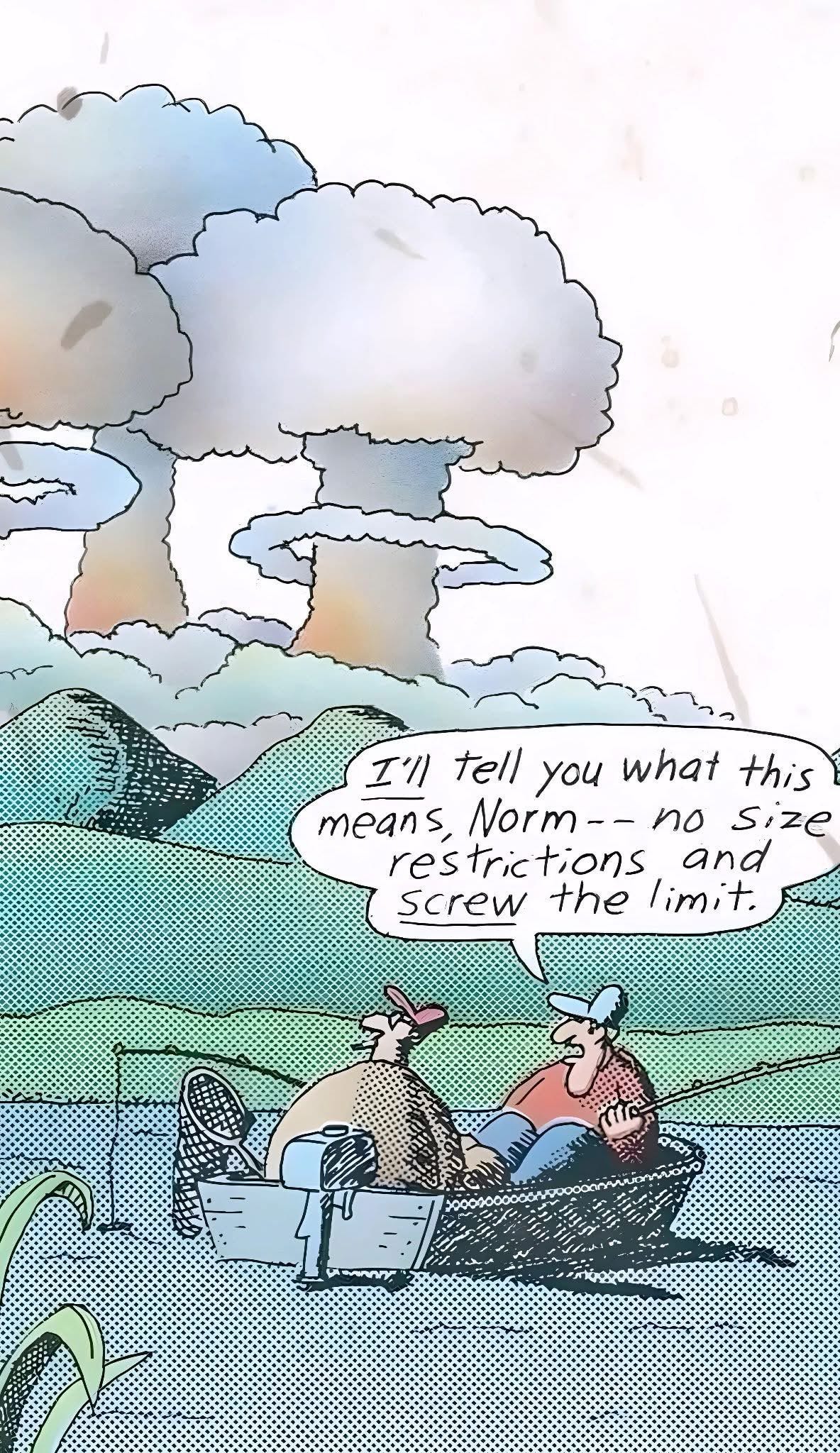

You, reader, are engaging in a Luddite enterprise right now. Not as crazily backward as reading a physical book or having Mr. Klein’s audacity to recommend three books every time you meet your friends (whether they ask you or not [!]), but an old timey medium for sure. The text you are reading is not going to change, while you are reading it or if you come back after lunch. If you scroll down, the only material you are going to find—stolen-MEMEs-or-random-pictures-strategically-inserted-to-interrupt-walls-of-text-at-intervals-the-author-estimates-will-be-pleasing aside—is the work of a single person. This blogging platform eschews flashy monkey business and brilliant advertisement.3 I started writing this at one point and then I stopped. There will be no updates. For some reason you are here, rather than on X or TikTok or Facebook or in front of the television because for any number of reasons you have chosen tacitly or otherwise to focus on something for longer than 30 seconds. We are thus in this thing together, writer and reader, and believe me I understand it takes constant energy to be faithful. The urge to post even more MEMEs or links to something funny or clever or timely…I have to say, it's irrepressible. That's part of the problem with a democratized medium. You can just say things. There's no editor. I found this great place online to order sausage. I’ll send you a link.

What would it sound like if you tried to communicate the message of the internet in the medium of prose? If you tried to write scroll. It would sound like the author had lost his mind.

Postman acknowledges himself as Marshall McLuhan’s heir, the latter’s famous observation being “the medium is the message”, which Postman revised to “the medium is the metaphor.” The thing everybody gets is that mediums change. We are not writing letters or leaving voicemails anymore. What Postman recognized was that the new medium is not a refashioning of the old. It is not (just) that we change how we communicate—mediums change how we think and how we understand the world. Trying to use social media accounts and text messaging like newspapers or phone calls is like Cervantes using cuneiform to write Don Quixote.4 You not only can’t go back,5 but you also can’t stay still. You must in fact go forward.

Postman was writing in the time of Reagan, who he argued, as others have since, brought celebrity and personal appeal, glamour and potential, to the fore in the realm of political competition. The successful presidential candidates since the Gipper have learned this (Slick Willie, W, Barry, Orange) the unsuccessful ones (Milquetoast, Crooked Hillary, Kambala) have not. An electorate raised on television and the Internet does not want facts and argument: they want emotion and feeling. Postman on politics in 1985: “Although it may go too far to say that the politician as celebrity has by itself made political parties irrelevant, there is certainly a conspicuous correlation between the rise of the former and the decline of the latter”. He would probably have a stroke after a single look at TruthSocial. And then later: “Censorship is not necessary when all political discourse takes the form of a jest.” Which of course made me think of Wallace. But first…

The medium dictates a register—right until it doesn’t. When Miguel was frittering away lazy afternoons in Seville consuming massive amounts of the medium of the day—written words—your correspondent imagines he had moment of clarity. A moment in which he saw the medium could be used for something that until that point it had not been: to capture real human interactions. It could capture something that no prior medium had captured. Oral histories and ancient texts were concerned with legends and myths, with stories about how the world would look if God peaked through the clouds and wrote down what he saw. Actions, narrative arcs. Cervantes didn’t do that. He pushed the reader right up next to the characters, right into the conversation. But he also put himself right there as well. Cervantes did not set out to tell a good story. He set out to create people, to let them loose and see what they would get into. There are no heavy-handed themes, no transparent metaphors, no poignant morality6…or at least nor more poignant than going about one’s daily routine. Don Quixote was the first sitcom: Cervantes has us coming back each chapter to see how the main characters will again get into adventures that reveal their absurd, meaningless and thus comic natures. They will become again who they are. No growing. No hugging.

“All that is required to make the idea that technology is neutral stick is a population that devoutly believes in the idea of progress. And in that sense, all Americans are Marxists, for we believe nothing if not that history is moving us towards some preordained paradise and that technology is the force behind that movement.” Postman

Don Quixote is crazily also the first attempt at what is now greyly called meta-fiction, with Cervantes speaking as the characters, to the characters, to the reader as himself, not as God. He’s in the book. He’s thrown out the register. There's a direct line, I would argue, from Cervantes through to Wallace or even Tarantino. Quixote and Panza hogging page after page with their…quotidian…dialogue, with each other and with people unfortunate enough to be in the path of Quixote's mad peripateity [sic]. This is not the author hanging out in third person omniscient. He’s right in there with us. The characters’ dialogue is the basis of the story, just like our internal dialogues with ourselves are the basis for our own. You can pick it up and any point and there’s stuff going on. You don’t need to know what the guy did yesterday to laugh at a YouTube reel of him falling down the front steps shoveling snow. To say Don Quixote exists outside of time is not the point. The plot, insofar as there is one, and certainly the dialogue and scenery, place it firmly in the 1600s. The point is you can be entertained for a few pages anywhere throughout the book without having to know or care what comes before or after. Just like when you run into someone on the street. A three-legged dog walks into a saloon. I’m looking for the man who shot my paw.

Wallace was often more explicit, if always slightly cheeky in his faux common-man hyper erudition, about what Infinite Jest7 was trying to accomplish. DFW wanted to get people, mostly Americans, and mostly Gen Xers to understand each other by the only means he thought effective, which was by reading books. Wallace was hyper aware of the threats to the medium of the novel and of the pernicious effect of television and the then neonatal Internet on social communities and moreover on the self. If the book is about anything it could certainly be said to be about how modern digital entertainment has made self-knowledge and self-fulfillment elusive. What Infinite Jest is about, however, is the topic of another essay. What I want to say here is what Wallace was trying to do when he wrote it, which was to trick the reader into doing some really challenging work by engaging with a really long and complex novel. He wanted to get people to pay attention for long periods of time. And so, Wallace wrote it in such a way that open to any page and you will find every paragraph impeccably tight and literary8—but also just plain fun. Wallace understood Postman's thesis and refused to reject the ancien medium.

Those last three paragraphs I wrote long hand in a notebook and then typed up on the computer. Most of the stuff I’m writing in the middle of the night, but I have to be honest with you, this part right now I’m dictating into my phone sitting at a traffic light. What would prose read like if someone just vomited the contents of their mind onto the page. Have the men in the white coats come for you yet, his grandfather asked him.

Each person waiting for permission. For someone to come up and grab them by the shoulders and shake them violently and shout in their face you do not have to live this way. What would DFW have Tweeted. Would you ever get a text from HDT.

The agreement between author and reader is that there's going to be a payoff: the longer I have to read, the better or more surprising or more frequent should be the payoff. We asked 10 random people if they were satisfied with their anti-dandruff shampoo. 10/10 replied: what the hell are you doing in my bathroom.

Social media has conditioned our minds to accept a complete absence of linear logic. To welcome hyperbole and contradiction. Genteel conversation and sensical narratives activate our Spidey Sense. We’re sure we’re being put on. When scroll introduces to me extreme weather, the Russian Ukraine war, the Oscars, male enhancement adverts, 90’s basketball highlights and maybe a scientific publication all in the span of 10 seconds, the ability to contextualize, ratiocinate, Fact Check, form and introduce for critique an opinion, read some more, phone a friend—in other words, to take the steps necessary to really understand and learn something—is nonexistent. And this is my expectation. Hence our comedians, whose original medium necessitates the toughest of payoffs be delivered every 30-60 seconds, have become our sages, our President is president because he is a comedian, and legacy media is a slur used to refer to long form journalism still practiced—quixotically—at your parents’ newspaper or magazine of choice.

Wallace understood the power of metafictional tricks to amuse the reader, but he was also very aware of not getting out of hand to make the trick itself the point or, worse yet, to make the hypertextual interlude pedantic and therefore not fun. His critique of self-service metafiction, written for critics and bookworms and weirdos and whose whole reason for existing was to be difficult and therefore to, by definition, be not enjoyable, was that it, this kind of writing, disrespected the reader on some level. As a child of television, his writing was littered with brilliant easter eggs. Postman: “The average length of a shot on network TV is only 3.5 seconds. The eye never rests, it always has something new to see.” It’s hard to explain puns to kleptomaniacs. They always take things literally.

There is no plot. Because the real world does not have a plot. Plots only exist in literature. If you take the plot out of literature, you get closer to real life. But then you get chaos.

The lie—or the windmill as dragon—we are currently charging is the mendacity of politicians and the media. This is a mistake. This is not the problem. The problem is we have been conditioned to be amused all the time, to the point where even calling this idea into questions seems absurd. Every aspect of our personal professional social political and yes leisure lives is geared towards entertainment. If it’s not amusing, what’s the point?

“Truth does not and never has come unadorned. [It is] intimately linked to the biases of forms of expression.” Postman, writing about alternative facts.

It is unwise to disrespect your audience by banging on about content they don’t care about. By not giving them what they came for. People have better things to do. They came for the information, not a winding unprofessional gratuitous smart aleck and maybe sophistic rant. Being long winded may be rude or lazy or arrogant or solipsistic. Being boring is unforgivable.

The MacGuffin in Wallace’s IJ is an audiovisual production contained on some sort of cartridge referred to as The Entertainment, which, when viewed, induces in the viewer an inescapable state of simultaneous euphoria and catatonia.

Here’s something else that’s not in the book: these corporations, the ones that run the country and the world and whatever, they have convinced all the people in said world to spend large amounts of money on devices. They’ve also convinced these folks to live their lives through these devices. The people in this world can no longer see without them. They learn from them, talk to them, talk through them, believe them, believe in them, they have a Pavlovian need to touch them ~1000 times a day, being completely dependent on them, these devices, in a way that is an order of magnitude more immersive than the type of relationship that any human has ever had with anything sentient like a dog or a cat and certainly not with another human being. If this is not the definition of love, then love does not exist. That? That is not in the book.

Musk’s superpower is not his accumulation of money. It is his accumulation of attention.9 Some guy on Twitter, who goes by the name Catturd and has ~3.6x10^6 followers and who looks a lot like some dude I went to high school with, is more influential than all the network news anchors combined. You will be given freely the thing that will destroy you. You will beg for more of it.

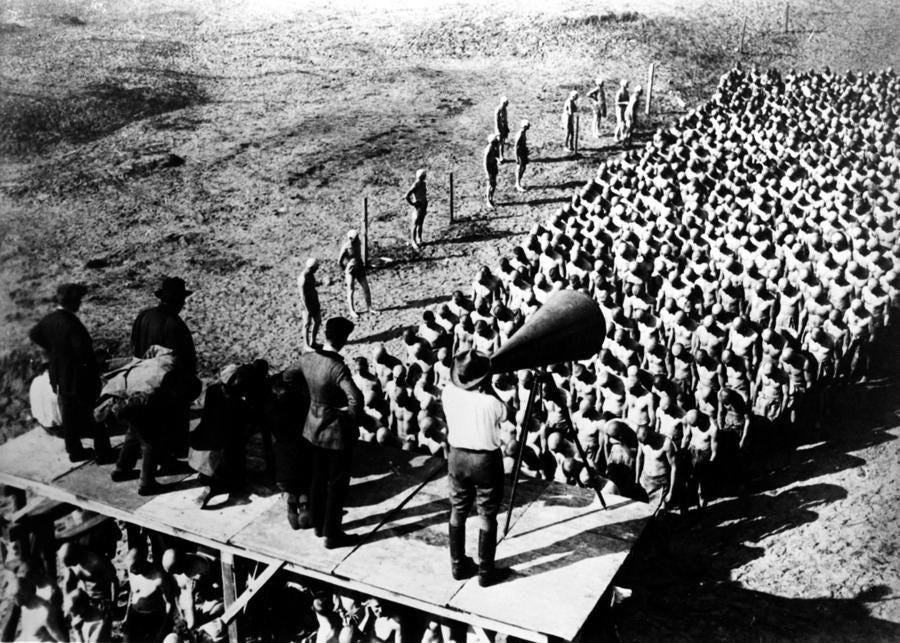

There are only so many things you can talk about, only so many things you can introduce, and expect people to stay with you. You have to cut. You have to focus. The FTZWS strategy perfected by Seinfeld millionaire S. Bannon is the first political mastery, like Goebbels before him, of the new medium. The constant onslaught of new real content, new fake content, speculation, inuendo, actual objective facts (these are essential—they must be blanched), known lies, hot takes, expert opinions, testimonials, research, bluff, insult, praise, storytelling, mischief, prayer, dreams, aspirations, memories, long lists of numbers and dates, hallucinations, predictions, a joke, a song, a tale. You have to flood the zone with shit, until everyone just taps out.

One thing in there, in Wallace’s book, about the guy who created this lethal entertainment: whatever motivated him to create it, also motivated him to put his own head in a microwave and then turn the microwave on. This is also not exactly what the book is about, but it’s in there.

At the top, the wind was biting and the sun painfully bright. The city stretched west and south and the sea or the horizon, I can’t be sure which, sheened beneath the clouds. It was there I started to get a cold sweat on the back of my neck, realizing this was my responsibility. I was the one with the constant circuitous distractive and discursive tangents. I had created the Internet. I was the reason that it is the way it is. The Internet doesn’t exist without me. Probably the world doesn’t exist without me. All of this was my fault and I was pretty sure I would fold under questioning. No matter. I descended a gentler route along the ridge to the lodge where Tall Paul had taken the lift to meet me for that beer. I had forgotten my wallet, so he spotted me. We rode the lift back down together before the sun set.

Back at the cabin, the fire now going, in the rocking chair holding a book I’m not reading, enjoying the din of human activity around me, I remove the phone from pocket and check the activity app. In airplane mode, my silent companion had recorded my steps. Had recorded my day. Was with me the entire time.

Amusing Ourselves to Death. Postman, Neil. Penguin, 1985. My copy is the 20th anniversary issue, with introductions both from Postman and his son, Andrew.

A redundant command, I admit. You are of course reading this online. Alas there is not yet a print option.

Substack’s editing software does, however, I will report, deliver a message of caution to the writer once a certain length has been eclipsed to the effect of “you are currently at X thousand words, which is the limit at which most people read on their phone and frankly speaking probably more than enough so why don't you call it a day and go back and cut some and get a life, for real bro.” If it hasn’t happened already, your correspondent will undoubtedly encounter and BLOW RIGHT PAST said warning in the current essay.

The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha. Cervantes, Miguel de. 1605-1615. My copy is a 2003 translation by Edith Grossman.

Postman (p84): Marshall McLuhan called “rear view mirror” thinking the assumption that a new medium is mostly an extension or amplification of an older one. Postman, and presumably McLuhan before him, thought this was a mistake.

Ok, there may be some of this mumbojumbo in there, but you are going to have to go look for it yourself if you're into that kind of thing.

Infinite Jest. Wallace, David Foster. Little, Brown & Co. 1996. The copy of mine I’m working from is a 10th anniversary paperback.

Although Wallace may never have admitted aloud anything so pretentious—he would always get digressive and self-conscious and seem like he was suffering from hyperthyroidism when addressing, to an interviewer, the concept of what real literature was—I think what he was doing was trying to show that he was in fact better than your Stephen Kings, John Grishams, Dean R. Koontzs, Dianelle Steeles, because he could write a captivating narrative, a goddamn page turner, about the quotidian and the bizarre alike, but he could do it in bulletproof prose that would make Nabokov blush.

Credit: Ezra Klein.